The War Powers Resolution and the Counter-Houthi Mission

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The Biden administration has a War Powers Resolution (WPR) deadline problem in connection with its campaign of airstrikes against the Houthis. The problem is that the WPR requires the president to terminate any use of U.S. armed forces introduced into hostilities within 60 (or, in the case of military need to protect the troops, 90) days unless Congress declares war or authorizes force. It appears that the administration introduced armed forces at least as of Jan. 11. That would mean that the administration would need to secure congressional authorization for the Houthi attacks by no later than April 11—unless it can find legal arguments that avoid this conclusion. This article examines four such arguments.

The Nature of the Conflict

U.S. and U.K. forces conducted a joint operation against Houthi targets in Yemen on Jan. 11 in response to the more than 30 Houthi attacks since Nov. 19, 2023, on commercial shipping and U.S. and partner forces in the Red Sea, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, and the Gulf of Aden. Since that initial use of military force, the U.S. has conducted eight more attacks on Houthi militants, as the Houthis have continued their attacks on U.S. forces and international shipping. These are the rounds of attacks that have been reported:

Jan. 11: U.S. conducts initial round of large-scale joint operations with the U.K., which used more than 150 munitions to target 28 locations in Yemen

Jan. 12: U.S. forces strike Houthi radar site (“follow on action” to the strikes with the U.K.)

Jan. 15: U.S. forces strike four Houthi anti-ship ballistic missiles

Jan. 17: U.S. forces strike 14 Houthi missiles

Jan. 18: U.S. forces strike two Houthi anti-ship missiles

Jan. 19: U.S. forces strike three Houthi anti-ship missiles

Jan. 19: U.S. forces strike Houthi anti-ship missile

Jan. 22: U.S. forces conduct second round of joint operations with the U.K., targeting eight Houthi locations and firing approximately 25 to 30 munitions.

Jan. 23: U.S. forces strike two Houthi anti-ship missiles

Statements from senior officials in the Biden administration since the Jan. 11 initial strikes reveal two things. First, these attacks are part of one coordinated effort to degrade Houthi capabilities and to deter additional Houthi attacks on international shipping and U.S. and partner forces. Second, the attacks are likely to continue for an extended, and indeed indefinite, period of time, until the Houthis relent. Reflecting this view, President Biden said on Jan. 11 that the U.S. would “not hesitate to direct further measures to protect our people and the free flow of international commerce as necessary.” The message from the Biden administration has remained remarkably consistent. A week later, President Biden stated that the attacks on the Houthis are “going to continue, yes.”

The Pentagon underscored these messages following the latest joint strikes in Yemen. An unnamed senior defense official said on Jan. 22 of the U.S. posture, “We stand ready to take further actions to neutralize threats or respond to attacks, ensuring the stability and security of the Red Sea region and international trade routes.” And in a press conference earlier in the day, Pentagon Deputy Press Secretary Sabrina Singh reiterated that when U.S. actions wind down “is really up the Houthis,” affirming the U.S. would “continue to take the necessary force that we need to protect our forces, to protect commercial shipping through the Red Sea, [and] through the Gulf of Aden.” And since the latest joint U.S.-U.K. attacks, National Security Council spokesman John Kirby and Pentagon Press Secretary Pat Ryder have reaffirmed the U.S.’s commitment to deterring Houthi attacks as long as they continue.

In response, the Houthis have vowed retaliation since the initial U.S. and U.K. strikes. Before the most recent U.S. and British attacks, a Houthi military spokesman said that “[r]etaliation against American and British attacks is inevitable, and any new aggression will not go unpunished.” And after the strikes, a Houthi leader, Mohamed Ali al-Houthi, wrote on X, “Your strikes will only make the Yemeni people stronger and more determined to confront you, as you are the aggressors against our country.”

The administration has twice reported to Congress, “consistent with” the WPR, on these strikes—once on Jan. 12 and again yesterday, Jan. 24.

The War Powers Resolution

Section 4(a)(1) of the WPR requires the president to submit a report to Congress notifying lawmakers within 48 hours of the introduction of U.S. forces into hostilities. Under Section 5(b) of the WPR, the president must “terminate any use of United States Armed Forces with respect to which such report was submitted” within 60 days of the issuance of that report, or the deadline for the submission of the report—absent congressional authorization for the military action or congressional extension of the deadlines. Section 5(b) also permits the president to extend the deadline if he notifies Congress in writing that the safety of U.S. military personnel requires this extension.

The White House’s Jan. 12 and Jan. 24 WPR reports to Congress related to the attacks against the Houthis did not (as is typical) specify that the reports were filed pursuant to Section 4(a)(1) of the WPR. Also, both reports justified the attacks based on the president’s constitutional authorities alone. Specifically, both reports stated: “I directed this military action consistent with my responsibility to protect United States citizens both at home and abroad and in furtherance of United States national security and foreign policy interests, pursuant to my constitutional authority as Commander in Chief and Chief Executive and to conduct United States foreign relations.”

The Biden Administration’s Options

At first glance, and assuming that President Biden extends the clock 30 days under Section 5(b), it appears that the administration must, as Section 5(b) says, “terminate any use of United States Armed Forces with respect to which such report was submitted (or required to be submitted), unless the Congress (1) has declared war or has enacted a specific authorization for such use of United States Armed Forces,” or (2) “extend[s] by law [the] sixty-day period.” That would mean that the Biden administration must get Congress on board by April 11 at the latest or terminate the use of force against the Houthis.

There are four legal moves the Biden administration might make to avoid the conclusion that the WPR requires termination of hostilities against the Houthis in April. (Brian Finucane canvassed versions of three of these arguments earlier this month in his broader analysis of the U.S. attacks in the Middle East.)

Statutory Authorization

The first approach would involve finding some extant congressional authorization to support the strikes, which would take the military action outside the realm of the WPR. The Obama administration made a form of this move in 2014 when it interpreted the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) to apply to the Islamic State. At first the administration relied on Article II to use force against the Islamic State. But as the WPR deadline approached, the administration switched and relied on its infamous expanded interpretation of the 2001 AUMF to apply to the Islamic State. That interpretation, while controversial, eliminated any WPR worry, since Congress was deemed to have authorized the action. The Biden administration could try something similar here, but it is not obvious to us what statute it might hang its hat on.

Probably the least bad argument for congressional authorization, believe it or not, is that the 2001 AUMF covers the operations against the Houthis. Which is not to say that it is a good or even a plausible argument; we think that applying the AUMF to the conflict with the Houthis is a much larger stretch than the stretch in 2014 to apply it to the Islamic State. The Islamic State grew out of al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), a Sunni group like al-Qaeda, that was founded by Abu Musaib al Zarqawi and that functioned as al-Qaeda in Iraq beginning in 2004 until around February 2014, when the groups split and became adversaries. The Obama administration argued that the emergent Islamic State had been covered by the AUMF since 2004 given AQI’s “direct relationship with bin Laden himself” and the fact that it “waged that conflict in allegiance to him while he was alive.” The administration concluded that in these circumstances, “the President is not divested of the previously available authority under the 2001 AUMF to continue protecting the country from [the Islamic State]—a group that has been subject to that AUMF for close to a decade—simply because of disagreements between the group and al-Qa’ida’s current leadership.”

The situation with the Houthis, a Shiite group, appears to be quite different. (We acknowledge that it is often very difficult for the public to ascertain the relationship between certain terrorist organizations.) The Houthis had no connection to al-Qaeda during bin Laden’s lifetime and have salient ideological differences with al-Qaeda affiliates in Yemen. However, the Houthis have cooperated in recent years with al-Qaeda elements in Yemen, at least in terms of communication and prisoner releases. But the group definitely did not grow out of al-Qaeda or fight closely alongside al-Qaeda, as AQI did for a long time. And we have seen no suggestion that the Houthis have ever been covered by the AUMF or ever fought as anything approaching a co-belligerent to any al-Qaeda affiliate. If these facts are basically right, it would be a huge leap beyond the rather large leap in 2014 to conclude that the AUMF applied to the conflict with the Houthis. And of course, the Biden administration did not rely on this sketchy argument in its WPR letter.

“Hostilities”

The Biden administration might also do what the Obama administration did in 2011 in connection with Libya: argue that the WPR limitations are not implicated because U.S. forces are not engaged in “hostilities” within the meaning of the WPR. This was a controversial argument back in the day, since the United States engaged with a NATO coalition by dropping thousands of bombing sorties over 227 days in Libya; since its operations in coordination with coalition forces resulted in the death of approximately somewhere between 8,000 and 11,500 individuals; and since the U.S. provided massive aerial intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance for the action as well. Nonetheless, the Obama administration argued in testimony by State Department Legal Adviser Harold Koh, the U.S action did not amount to “hostilities” because the military mission was “unusually limited” and involved “limited exposure for U.S. troops and limited risk of serious escalation and employ[ed] limited military means.”

The Biden administration might look to this precedent. A key move would be to assimilate the White House Office of Legal Counsel’s constitutional standard for war—which turns mainly on the risk to U.S. troops and the threat of escalation—into the meaning of “hostilities” in the WPR. This argument would, as one of us has argued with Matthew Waxman, effectively eliminate “WPR limits for much light-footprint warfare”—that is, warfare from a distance in which U.S. troops face little danger. But while there is a precedent on the books, which counts for a lot within the executive branch, there are differences as well that render this WPR argument significantly harder to make in the current context.

First, the Houthi strikes, unlike the ones in Libya, come in the context of persistent attacks on U.S. armed forces and U.S. commercial ships. As an unnamed senior defense official said during a briefing following the Jan. 22 joint U.S.-U.K. strikes: “U.S. military and merchant vessels have faced persistent threats from Houthi missiles and UAVs. Notable incidents include a January 14th attack on the USS Laboon and a barrage of nearly two dozen munitions on January 9th targeting U.S. Navy and U.S.-flagged merchant vessels.” This position contrasts sharply with a key precedent that Koh invoked in the Libya episode: the Ford administration’s view that the term “hostilities” in the WPR is limited to “a situation in which units of the U.S. armed forces are actively engaged in exchanges of fire with opposing units of hostile forces.” Koh invoked that precedent because it more or less applied to the Libya situation. But it definitely does not apply to the Houthi situation. Relatedly, we also think it would be hard to argue here that U.S. troops have not been “introduced” into hostilities.

Second, the threat of escalation—which is a different part of the constitutional standard, and which Koh also invoked in 2011 related to the WPR—is obviously much greater here than in Libya. There was no such plausible threat in Libya. Yet in the current conflict, we have seen escalation with the Houthis already and threats to continue escalation. And there are several dangerous proximate military threats as well.

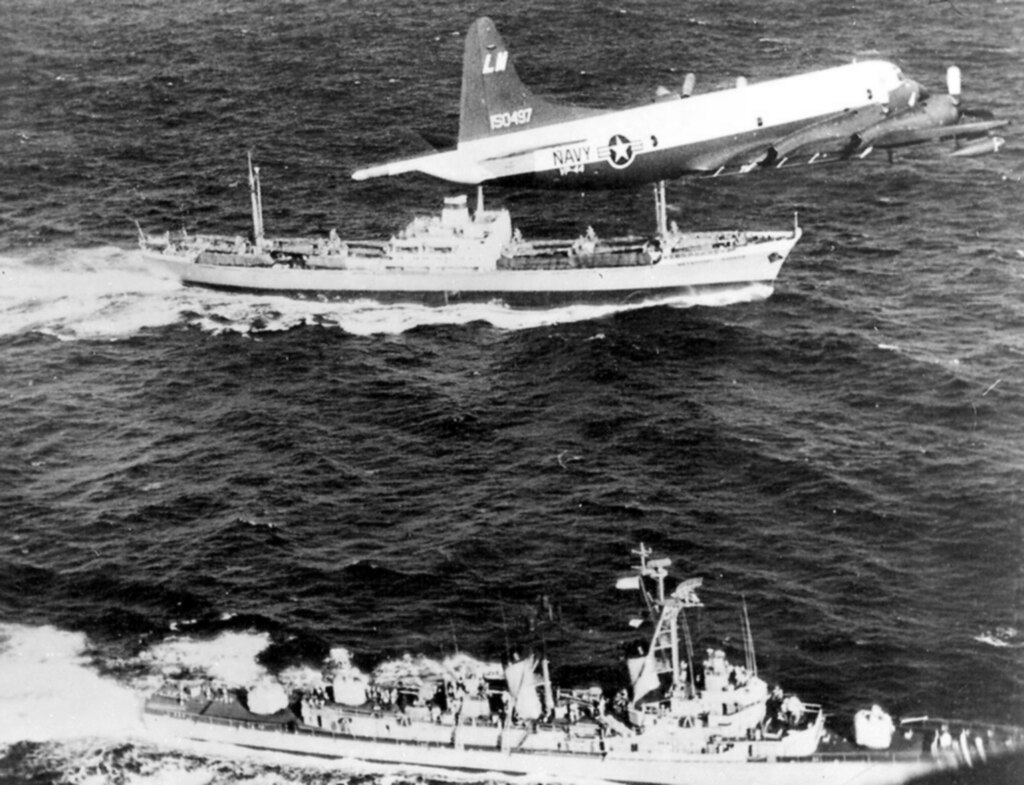

Renewed Clock

The administration might also argue that each attack on the Houthis—or some subset of the attacks—is a discrete and new set of “hostilities” under the WPR, which would mean that the clock would restart with each attack (or some subset of attacks), and never reach 60 days. One of us speculated that this is what the Obama administration was considering in the summer of 2014, in its initial strikes against the Islamic State, when it sent a flurry of WPR letters to Congress more or less following each round of strikes against the Islamic State. The Reagan administration during the 1987 and 1988 Tanker War also appeared to take something like this approach in connection with its fight against Iranian forces after the U.S. agreed to reflag Kuwaiti ships to deter attacks on vessels from Iran.

This argument is premised on the idea that the duty to terminate in Section 5(b) applies to “any use of United States Armed Forces with respect to which such report was submitted” (italics added for emphasis). If a use of armed forces is defined narrowly as a discrete round of strikes rather than a continuous though intermittent engagement, the WPR clock might run and end for that discrete round of strikes and then start afresh with a new round of strikes, which means the 60-day limit would never be reached. The Biden administration might argue, for example, that the attacks reported in the Jan. 12 letter are a different and discrete “use of United States Armed Forces” from the attacks that triggered the Jan. 24 letter, and that the WPR clock starts anew with respect to the Jan. 22 attacks that were reported on Jan. 24.

Marty Lederman argued years ago that the WPR rules out this argument because “[t]he text of the statute indicates that, no matter whether the President submits one or a dozen WPR reports, the 60-day clock would appear to continue to run–even if the Armed Forces cease the use of force for days or weeks at a time–if U.S. Forces remain in a ‘situation[] where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances.’” This is a very plausible reading of the text of the statute and one that comports with its aims.

But even if the statute permits the discrete-reporting approach, it has weaknesses as applied to the current context. One weakness is that the administration has portrayed the strikes against the Houthis all month as part of a singular engagement of hostilities. Another weakness is that the administration has not filed discrete letters for each of the nine rounds of attacks against the Houthis. (The Reagan and Obama administration episodes above involved letters that were filed with respect to many rounds of attacks but not necessarily every one.) The administration did, to be sure, describe the Houthi strikes in both WPR letters as “discrete,” and perhaps it did so to try to preserve the salami-slicing argument. But the absence of letters for the strikes on Jan. 12, Jan. 15, Jan. 17, Jan. 18, two on Jan. 19, and one on Jan. 23 is nonetheless telling. Moreover, the administration’s two letters did nothing to suggest that the strikes that led to the letters were completed events. This contrasts with the Reagan letters; four of the six letters President Reagan issued notifying Congress of these U.S. actions included the statement that the incidents were “closed,” thus suggesting that those actions were deemed discrete uses of the armed forces and not part of an extended singular set of hostilities.

Article II Override

Finally, the administration could argue that the WPR limitations in this context are unconstitutional. The argument would be different from the old argument, made by some past administrations, that the termination provisions of the WPR are in general unconstitutional, in violation of Article II. The argument today would be narrower and would run something like this: Congress can perhaps limit the president’s military powers as the WPR does with respect to offensive uses of force. But the president has long been endowed with significant self-defensive powers, including the powers to protect U.S. persons and troops abroad. Congress cannot, the argument would go, require the president to stop protecting U.S. troops that are under attack. This argument might be couched in the form of constitutional avoidance, as a way to read the less-than-precise WPR provisions to avoid constitutional difficulties. It could also be used to supplement some of the arguments above.

This constitutional argument is not implausible given the president’s broad and acknowledged self-defense powers. Yet the argument would amount to a sweeping circumvention of the WPR, since the president has broad authorities independent of discrete force authorizations to place troops around the globe, where they are exposed to potential attacks, as is happening now in many places in the Middle East.

Conclusion

The almost three months between now and the possible running of the WPR clock is a long time. Maybe the conflict with the Houthis will end by then. Or maybe the Biden administration can convince Congress to get on board for its uses of force. We are skeptical of the latter possibility. In addition to the usual inertia problem in Congress, and to Congress’s not wanting responsibility for war powers decisions, the Biden administration might not want to seek overt congressional support. Not only would that effort take away resources from other important goals. It would also significantly raise the public stakes in the various conflicts in the Middle East if Congress were to formally authorize a war against the Iran-affiliated Houthi movement.

All of which is to say that administration lawyers will be under enormous pressure to find a vehicle for the continued use of force after April 11 if the conflict persists until then. The poorly drafted, loophole-filled WPR, past executive branch practice, and the self-defense posture of the engagement with the Houthis, give them several options, none of which is entirely clinching.

-final4d43.png)